Less how, more what

I’ve been really fortunate in my new position to have an inside look at some of the artificial intelligence technologies currently emerging, and they are impressive. It has me thinking quite a bit about the impact they will have in the reasonably near term. With the rise of MOOCs, a lot of thought has been going into how we teach, but I’m beginning to think we need to be spending more time on what we ought to be teaching.

The Atlantic recently covered a paper that estimated the likelihood of various job sectors being replaced by computerization and automation, and a lot of the predictions are not surprising—transportation, manufacturing, agriculture and administrative support are all on the chopping block. Management, STEM, education and healthcare, in the paper’s estimation, are all relatively safe jobs to have when the hordes of animatrons come calling. Good news for me, I suppose.

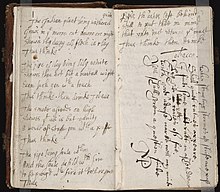

From Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael A. Osborne’s paper, “The Future of Employment: How Susceptible are Jobs to Computerization?”

I am, though, less interested in replacement than I am in how these technologies will change the nature of the jobs they don’t replace. My colleagues at MIT have done a great job of thinking about how MOOC technologies might change the nature of teaching, eliminating the rote learning and freeing up faculty and students for more substantive interactions. What does this say, then, about the way we should be preparing our future educators? The future of education seems to be less about delivering an effective message to a large body of listeners in a live format, and more about mentorship and one-to-one support.

How this might change the job of medical professionals? AI, at least as I’ve seen its potential so far, will likely be very good at differential diagnosis and the development of optimal treatment plans. As more and more data—such as individual genetics, and deep biochemical understandings of how drugs work—becomes available, there will be less and less guesswork involved in these areas, and more and more need for computational power in assessing the data and keeping up with emerging knowledge. A physician will still review and approve diagnosis and treatment plans, but the heavy lifting will be done by AI.

So what is the role of medical professionals? I’m sure there will be other areas, but one clear focus will be on execution, the ability to deliver the appropriate care at the highest level of quality, motivating patients to adhere to their treatment regimes, minimizing avoidable complications and infections, and managing care at a higher level across the lifetime of a patient. In Atul Gawande’s essay “The Bell Curve,” he highlights the way that better execution with the same science can generate significantly better outcomes for cystic fibrosis patients. Especially with the increased focus of cost reduction and improved quality in medicine, this kind of focus on high-level execution will become a larger and larger part of the work of medical professionals.

This also demonstrates an important role for openness in the future of medicine. We’ll need to train medical professionals to be better at execution in medical school, but improving outcomes is also a matter of sharing the tacit knowledge gained through experience and trial and error over time. This means that practicing clinicians need to learn from each other on an ongoing basis. Gawande’s essay does a great job of highlighting the importance of openness in sharing best practices, and open sharing projects like OPENPediatrics are ideal forums for such exchange. By sharing best practices from a wide range of cultures and resource settings, we help to share the tacit knowledge gained by clinicians working in these diverse settings, tacit knowledge that makes the difference between very good care and the very best.